‘This Is Unprecedented’: Why America’s Housing Market Has Never Been Weirder

from The Atlantic

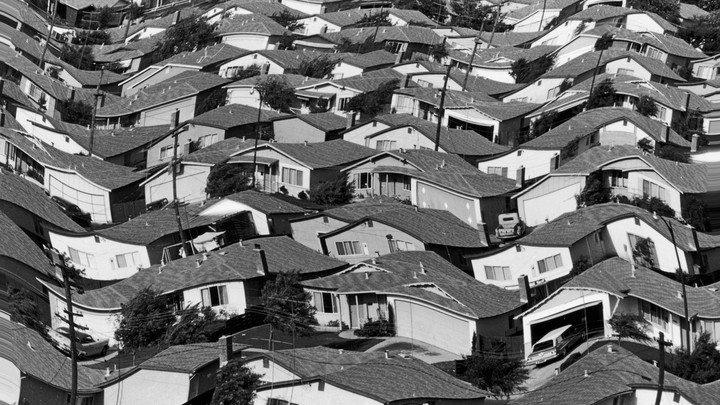

‘This Is Unprecedented’: Why America’s Housing Market Has Never Been Weirder

In America’s largest, richest cities, home prices and rents are going in opposite directions.

JOE MUNROE / HULTON ARCHIVE / GETTY / THE ATLANTIC

In almost any other year, a weak economy would cripple

housing. But the flash-freeze recession of 2020 corresponded with a real-estate

boom, led by high-end purchases in suburbs and small towns. Even stranger, in

America’s big metros, home prices and rents are going in opposite directions.

Home values increased in all of the 100 largest metros in the U.S., according

to Zillow data. But in some of the richest cities—San Jose; Seattle; New York;

Boston; Austin; San Francisco; Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles; and Chicago—rent

prices fell, many by double-digit percentages. In many cases, the gap was

absurdly large. In San Jose last year, home prices rose by 14 percent (the

sixth-largest increase in the country) but the area’s rents fell 7 percent (the

sixth-largest decline).

“I can’t think of a time when anything like this has happened,” Jeff

Tucker, the senior economist at Zillow, said of the divergence between rental

and home prices. “This is unprecedented.”

What’s going on? Some observers have

pointed to the severe shortage of single-family houses that

has resulted from the slower pace of building in the U.S. since the last

real-estate crash. Short supply is clearly pushing up housing prices. Others

point to plummeting interest rates that have encouraged people to seize the

opportunity to get a cheap mortgage. And then there’s the wave of new young

families seeking more permanent housing, as more Millennials enter their 30s.

In the last year, a lot of middle- and high-income

households took advantage of the pandemic to accelerate their plans to buy

first homes, second homes, and vacation homes. The typical 2020 homebuyer made nearly $100,000, a significantly higher income

than the average homebuyer had in past years. “The pandemic and the feeling of

not having enough space combined with low mortgage rates gave a lot of

higher-income families a reason to pull forward home purchases that they were

thinking about making in the next few years,” Tucker said. Plus, many of these

families were competing to purchase the same sorts of houses: Something bigger

with extra rooms to convert into work-from-home offices, a large

outdoor space, and, whenever possible, a pool.

As the COVID-inspired flight to larger houses boosted

home prices, the pandemic took a sledgehammer to urban amenities, and downtown

rents fell. Restaurants, bars, and museums have closed, and remote work has

made living close to the office less valuable. The typical new entrants into

cities, who would usually absorb any excess supply, have all been punished by

the pandemic in their own way. Immigration has declined, and some immigrants

working in COVID-affected industries have had to move or double up with family. Many

young college graduates have waited out the pandemic at a parent’s house. And

transient residents with the option to decamp temporarily to the suburbs have

done so. It’s all there in the U-Haul data: Arrivals to New York fell 35 percent last year, according to the

company, and no state saw more net emigration than California.

All of this has crushed demand for rented apartments in cities. But

something else has accentuated this historic divergence between downtown rents

and suburban housing prices: the quirky habits of the Millennial generation.

“There are an unusual number of

people around age 30 in America right now, and they have been unusually likely

to live in central cities,” Tucker said. Indeed, the number of 30- to

39-year-olds in America is about to reach its highest point in history; and

those are prime home-buying years. One analysis of New

York City by the real-estate website StreetEasy found that rents, while

increasing somewhat in the low-income parts of the city hit hardest by the

pandemic, plummeted in richer neighborhoods. That fits one of the big stories

of the pandemic: High-income Millennials using 2020 to trade their downtown

apartment rentals for urban and suburban homes.

This strange moment for American housing isn’t all

bad, though—and, in a few years, some very good things could come from it. A

historic imbalance between rents and home prices could set the stage for an

urban renaissance led by younger and more middle-class residents. The big drop

in Manhattan rental prices is already luring back younger residents. For those who

love cities—and I do—downtown living is a steal right now, and New York City in

particular hasn’t been this good a deal in decades.

According to Chris Salviati, an economist with the

online rental market Apartment List, rents are rising again in almost all of the hardest-hit rental markets,

including San Francisco, Boston, and Washington, D.C. As rents increase, so

will buyer’s remorse. We are already seeing the emergence of a new genre of

feature profile in major newspapers: the city slicker who moved to the suburbs, and hates it there.

One needn’t frame every story as a tale of generational warfare, but the generational angle to this story might be the most enduring one. The last decade has punished Millennials with a Great Recession, a slow recovery, and a housing shortage. But the next decade could see Generation Z moving into cities that offer great bargains for young residents, even as they benefit from a booming economy, full employment, and a surge in housing construction.

original article here: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/03/why-are-housing-prices-and-rents-down/618212/

Comments